On this day the Lord has acted. We will rejoice and be glad in it (Psalm 118:24)

We are not good at predicting the future. Take this recent example. Early in the Covid-19 pandemic it became clear that life as most knew it was changing: masks, working from home, Zoom classes, social distancing, on-line church, not seeing loved ones, etc. A group of scholars who share an interest in understanding how social and behavioral science can best inform public policy saw a golden opportunity. Last April (2020) they began a large-scale study to track the degree to which specialists in a wide-ranging number of fields in the social sciences accurately predicted the impact of Covid on a series of psychological and behaviour domains—life satisfaction, prejudice, loneliness, violence. They also studied how accurately laypeople (in this case average Americans) predicted the impact of the pandemic. (See, Michael Varnum, Cendri Hutcherson, Igor Grossman, Everybody was wrong about the Pandemic’s Social impact.)

So how well did both groups do in predicting the impact of the pandemic? Not well. Experts fared no better than laypersons. More than half of each group misjudged the direction of change in various categories (lower life satisfaction, higher rates of loneliness, lower rates of violence, etc.). In each group predictions were off by at least 20 percent. How so? Both experts and laypersons thought changes in these categories would be more extreme than they seem to be.

You can read the article about the study if you wish, agree, or argue with its conclusions. Post it or blog about it. My point here is this: we are not good at predicting the future. Anecdotally, if you had asked me when I was 30 to predict where I would live and what I would be doing 30 years later, my answer would only support my thesis.

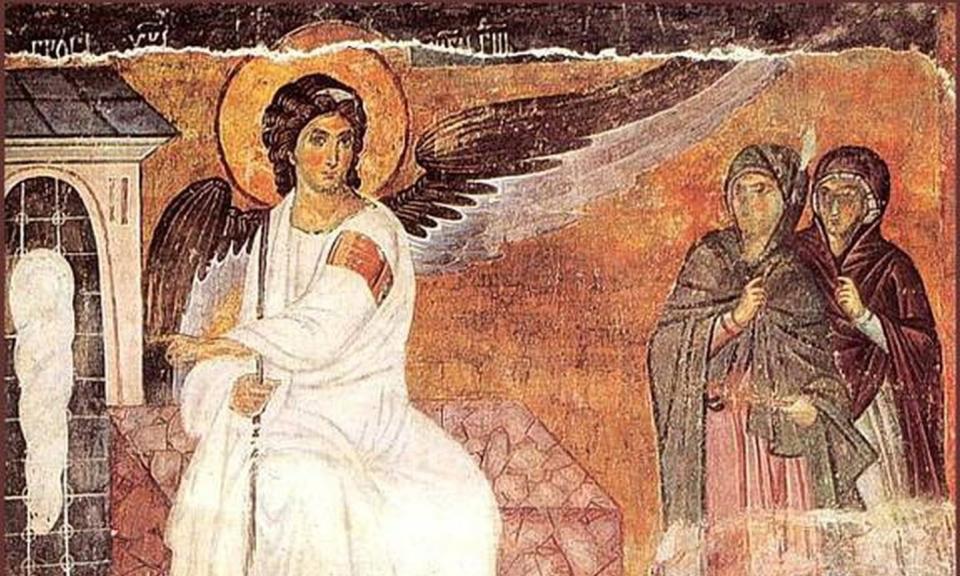

The women who came to Jesus’ tomb, likewise, were not good at predicting the future. They expected and had prepared for a corpse. They had accepted the fact that death had prevailed. That death and its henchmen had obliterated the future they’d hoped to share with Jesus and the other disciples.

But as they peered into the empty tomb, holding their now useless jars of spices and ointments, they were the first to witness the future secured in God’s decisive actions. Death will not prevail. Jesus is raised, humanity is redeemed, creation is renewed.

Oliver O’Donovan in Resurrection and the Moral Order argues that God has created—and thus we live—in a universe, not a multiverse: one coherent redeemed whole. Creation is an intelligible whole and it is within it, within its ordering and its telos that humanity is placed and thus receives its purpose and future. “If any of you could break my covenant with the night, so the day and night would not come at their appointed time, only then could my covenant with my servant, David, be broken” (Jer. 33:20). The empty tomb is God’s final and decisive Word on His created order, all of it. In the resurrection of Jesus, God has stood by His creation. God has not let it come to naught. Through Christ’s resurrection and ascension God’s has redeemed the whole thing.

What is our response to a future we can trust—if not predict—because of God’s raising of Christ? The church, O’Donovan writes is a glad community (The Desire of Nations: Rediscovering the roots of Political Theology). Gladness, rather than an emotion, is a path we walk together, a way of life. “A disposition of the affections appropriate to the recognition of God’s creative goodness.” We are what God has made us (Eph 2:10). Here is the source of our gladness and delight.

At the centre of God’s redeemed creation stands the risen and ascended Christ. There is no future for the universe which is independent from its redemption in Jesus Christ. Trusting this makes the future predictable in a way that is unshakable. Not in terms of what will happen in this or that place or generation—this we cannot know and are bad at predicting—but in what we are to do in any and all situations. With gratitude and humility we actively participate in Christ’s sacrificial love for the universe: friend, enemy, neighbor, and creation alike.

We have received the way forward in the risen and ascended Christ. And so, we follow.

About

Annette Brownlee is Chaplain, Professor of Pastoral Theology and Director of Field Education at Wycliffe College.