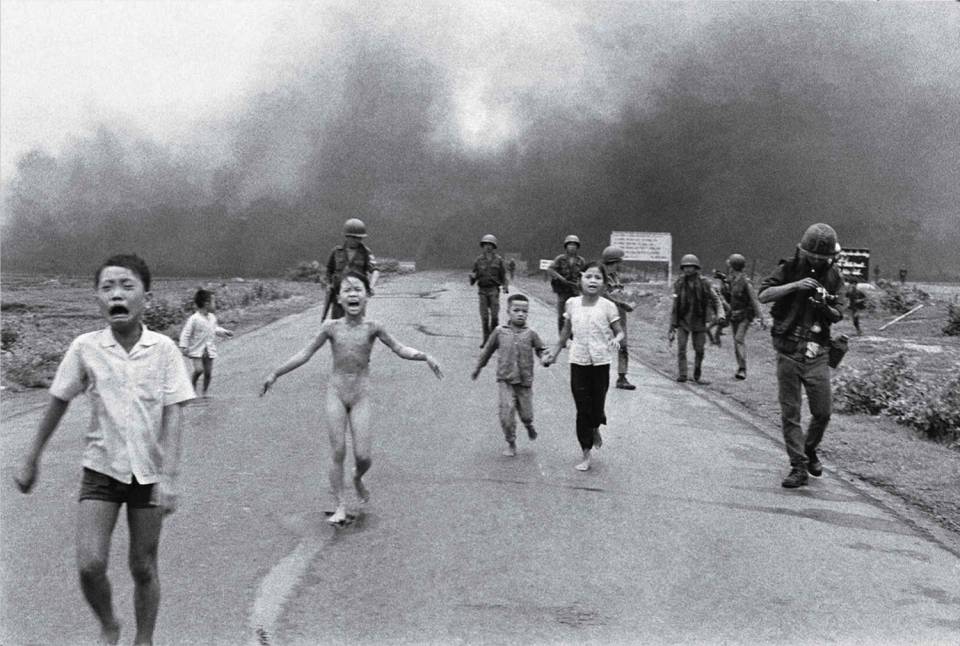

If you’re near my age, or older, you likely remember seeing this photo in a newspaper in June 1972, probably on page one. It shows nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc, her clothes and most of her skin burned off by a napalm bomb that had just been dropped on her village from a South Vietnamese Skyraider military aircraft. Her face distorted by pain, she’s running down Route 1 in Trang Bang, South Vietnam, trying to shake off the agony. But napalm sticks, and you can’t outrun it.

When I first saw that picture, it seared my soul. It still does. Nothing hurts my heart more than a child in needless pain. For many of us, it encapsulated the tragic mistake of the war in Vietnam, and, really, of all wars.

The young Vietnamese news photographer who took this iconic picture, and who would later win a Pulitzer Prize for it, saved Kim Phuc’s life. He bundled her and others into his Associated Press truck and rushed them to a hospital in Saigon. When the hospital workers initially refused to accept her — with most of her body covered in third- and fourth-degree burns, and her muscles and inner organs partially exposed, she had virtually no chance of survival — he displayed his press credentials and threatened them with bad publicity.

Last semester a Vietnamese student of mine wrote an essay about Kim Phuc and “moral injury,” and alerted me to the existence of her 2017 autobiography, Fire Road. In it, she writes about the remarkable series of apparent accidents, which she attributes to God’s providence, that placed her in Vietnam’s only medical unit for pediatric plastic and reconstructive surgery. She spent the next fourteen months there, undergoing sixteen surgeries and agonizing daily treatments.

The doctors kept her alive, but couldn’t save her from terrible constant pain for the next forty years. Nor could they help her re-enter society as a normal child. Her scarring left her with something more like buffalo hide than human skin. Former friends avoided her. Seeing herself as ugly and different, she felt isolated.

As the tenth anniversary of the bombing approached, the Communist government of Vietnam identified her as a propaganda bonanza. It conscripted her for never-ending rounds of press interviews in Vietnam and in other Communist countries. When so-called translators pretended to tell journalists what Kim Phuc was saying, they followed a government script. And she came under almost constant surveillance from government-appointed minders.

But one day she evaded her minders, and hid in the Saigon library. There she discovered the New Testament, and she was both shocked and drawn in by what it said. She found an opportunity to talk to a Christian pastor, and asked questions. She attended his church when she could, and was mentored by a member of his congregation. There, at Christmas 1983, she invited “Jesus, the One and Only, into my heart.”

Her parents stopped speaking to her.

She diligently studied the Scriptures and prayed. She slowly began to overcome fear, and bitterness, and hate. She learned to face new problems with faith.

In October 1992, on a flight between Moscow and Havana, as arranged by the Vietnamese government, she and her husband took advantage of a fueling layover in Gander to defect. Since then she and her husband have lived in the Toronto area, where they have raised a family. In 2015 she underwent another round of surgeries in Miami, and she’s now often free of pain.

Kim Phuc created The Kim Foundation International, which raises money for child victims of war. Currently it’s helping Ukrainian children who are resettling in Canada.

She has the heart of an evangelist, and Fire Road is a winsomely evangelistic book. She writes:

Had my suffering actually been the catalyst to bring me into God’s family? Could such a thing be true? In my heart, I knew the answer. Those bombs led me to Christ. Armed with that information, my passion soared for helping others make the connection between their pain and God’s ultimate plan.

“Thank you, God,” she writes, “yes, even for that road.”

As a church historian, I find that some of the most moving and meaningful sources I read are Christian autobiography. Most influential of all is Augustine’s Confessions. In it, he searches his heart, in God’s presence and ours, on the premise that we can’t know God unless we know ourselves, and we can’t know ourselves unless we know God. But both God and the self are mysteries. “Who am I, and what is my nature?” he writes (IX.i.1); and “who, then, are you, my God?” (I.iv.4) As a result, the Confessions isn’t Augustine’s story of how he heard God and obeyed, which would amount to an exercise in self-justification. Instead, it’s mostly his confession of some of the ways in which he has been errant, while recognizing that, in his many misdirections, he was never separated from God’s love. For God is “truly present” but “secret” (I.iv.4). God has piloted him, but “most secretly” (IV, 14, 23). God knows the cause why Augustine does things, but doesn’t disclose it (V.viii.15).

There are many reasons to doubt the historical veracity of the episodes recorded in the Confessions. As Augustine elaborates in Book X, he has looked for his true self in his memory, but memory is a storehouse of an innumerable multiplicity of ideas and images: and that means that, when he looks retrospectively for patterns and meanings, and selects from them, organizes them, and turns them into prose, with a purpose in mind, he’s constructing, at best, only a plausible version of his past. And today we recognize, perhaps more than Augustine, that memory isn’t really just a storehouse; it actively invents, represses, and adapts the past.

That said, the Confessions stands as a powerful witness to God’s love and involvement in our lives, even if we have no way of verifying its narratives of specific past events.

It’s also an invitation to us to look within ourselves, acknowledging that we, too, are a mystery to ourselves, and that, in order to begin to fathom that mystery, we need to engage as well with the mystery of God.

This brings me back to Fire Road. Maybe it’s not all precisely true. Reading it I often thought, “Others in Kim Phuc’s life might have different perspectives on this point,” or, “That situation was probably more complex than Kim Phuc could have known,” or “She may have a hidden agenda in that statement.” Her story isn’t historically unimpeachable; no history is. But it has unassailable authority as her story, as her offering of her insight into God’s love and the meaning of her life, a life whose most compelling mystery is a moment in 1972 when it was abruptly threatened and unexpectedly preserved.

So Kim Phuc’s story is engaging, affecting, inspiring. But so is yours, in its different way. I give thanks for all the stories we tell that grow from an honest searching of memory, in the presence of a God who is truly present, but works in us secretly.