Today marks the centenary of the birth of John R.W. Stott (1921-2011). Identified by Time magazine in 2005 as one of the world’s “100 Most Influential People,” John R.W. Stott was a legendary figure in the modern global evangelical movement. Evangelicals of various stripes claimed him as their own. To Billy Graham, he was a fellow evangelist. To decades of students in the Inter-Varsity movement, he was an apologist and mentor. To missiologists and church leaders in the Majority World, he was a statesman, diplomat, and the framer of the 1974 Lausanne Covenant. And to millions who have heard his expository preaching or who have read his books and commentaries, he was and continues to be a trustworthy and compelling guide to the divinely given truth of Scripture and what it means to live as a radical disciple of Jesus Christ in today’s world.

But many in North America who are familiar with his name express surprise to learn that he was an Anglican. He was, in fact, baptised, confirmed and ordained in the Church of England in London, and his remains rest in a Church of Wales graveyard on the Pembrokeshire coast. He served for nearly fifty years as Chaplain to the Queen. There are many who would credit John Stott for the resurgence of evangelicalism in the Church of England, and one historian, the late David L. Edwards, has even claimed that he was “the most influential clergyman in the Church of England during the twentieth century,” apart from Archbishop William Temple. His leadership to the church was recognized in 2006 when he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

John Stott’s identity as an evangelical finds its origins in a conversion experience as a seventeen year-old schoolboy when he knelt by his dormitory bed, confessed his sins, thanked Christ for dying for him, and asked Jesus to come into his life. His father, an eminent cardiologist and major general in the Royal Army Medical Corps, had hopes that he might distinguish himself in the diplomatic service. His leadership abilities were already evident in his role as head boy at Rugby school. But under the influence of a Scripture Union chaplain, he set his sights on ordination. He went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, for Modern Languages, and stayed on to read Theology at Ridley Hall. He was made Deacon in 1945 and took up a curate’s post in All Souls’, Langham Place, the church he had attended with his mom as a boy in London.

His crown appointment as Rector there in 1950 marked him as an emerging leader in the evangelical wing of the church. At the time, evangelicals were a despised and fractured lot. On the one hand, there were the so-called “liberal evangelicals,” those who professed an individualistic piety related to the cross, but who were not comfortable with a substitutionary view of the atonement, and who were open to the claims of modern scientific enquiry of the Bible and its transmission. On the other hand, the “conservative evangelicals” were regularly described as defensive, anti-intellectual fundamentalists. John Stott’s own convictions clearly fell within the compass of conservative evangelicalism, but he regarded the unflattering descriptions as both a caricature and as offensive to the integrity of evangelical Christianity, which he claimed was “bible Christianity,” and in the mainstream of historic, orthodox, and Reformed belief. He sought to redeem both the perceptions and place of conservative evangelicals in the Church.

In the first place, he took great pains to distinguish evangelicalism from fundamentalism, and articulated a theology that featured a nuanced view of biblical inspiration, an openness to fellowship with Christians from other denominational traditions, and a view that was not tied to one millenarian eschatological scheme. Secondly, he believed that the church needed to become more, and not less, involved in the affairs of the church and the world. He was not blind to the church’s shortcomings and faults, but claimed that while the Church of England’s formularies and Prayer Book gave expression to the Reformation principles of sola scriptura, sola gratia, sola fide and solus Christus, he was able to remain a member in good conscience.

There was a famous standoff between him and the renowned Free Church evangelical, Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones, at a 1966 conference of evangelicals in London. In the opening address, Dr Lloyd-Jones was understood by many to have issued a call to evangelicals to depart from their gospel-compromising denominations to form a united evangelical fellowship. This prompted John Stott to step out of his role as Chair of the gathering and issue a rebuttal to the good Doctor’s appeal. Both Scripture and history were against his position, he averred. His intervention served to consolidate Anglican conviction about staying within the Church of England, but also precipitated division within the broader evangelical community.

In 1967, John Stott put his energies into planning the first National Evangelical Anglican Congress, meeting in Keele. Attended by more than a thousand clergy and lay people, it proved to be the beginning of an Anglican evangelical reformation as evangelicals repented of their isolationist tendencies and pledged to come out of their ghettos in order to become more engaged in the affairs of the church and address the political, social, and economic issues facing the world. The next decade saw a steady rise in the number of evangelicals participating in church commissions and writing on matters such as liturgy, education, urban problems, and questions of morality and law in secular society. A new generation of evangelical theologians and biblical scholars emerged. The prominence today of Tyndale House in Cambridge (a centre for biblical studies) and of a great number of evangelicals who currently hold senior academic and ecclesiastical posts both in the UK and abroad, has been achieved in large part by John Stott’s tireless and articulate promotion of the evangelical cause, and through his encouragement of younger evangelical leaders.

John Stott’s legacy in the Anglican Church is that he has left us a bold apology for an evangelical theology that is apostolic, Christological, biblical, and personal. But this has not been enough to keep the church together. Less than a decade before his death, he said in an interview, “During the last 50 years I have seen the evangelical movement grow in size, scholarship, and influence. What worries me now is that we are more a coalition than a party.” A coalition is a temporary alliance brought about by the desire to achieve some practical end, and he was discouraged by how evangelicals had come to politicize the church.

There are those who see the fragmentation of Anglican evangelicalism as the consequence of his own policy of engagement. They maintain that if evangelicals had listened to Dr Lloyd-Jones, they would have avoided the dilution of conviction engagement brings. But the painful reality is that pride and rebellion resides in every human heart, and if there is any hope for an Anglican evangelical future, it will be as evangelicals put their differences aside and, in John Stott’s words, “take [their] place humbly, quietly and expectantly at the feet of Jesus Christ, in order to listen attentively to his Word, and to believe and obey it.”

ABOUT

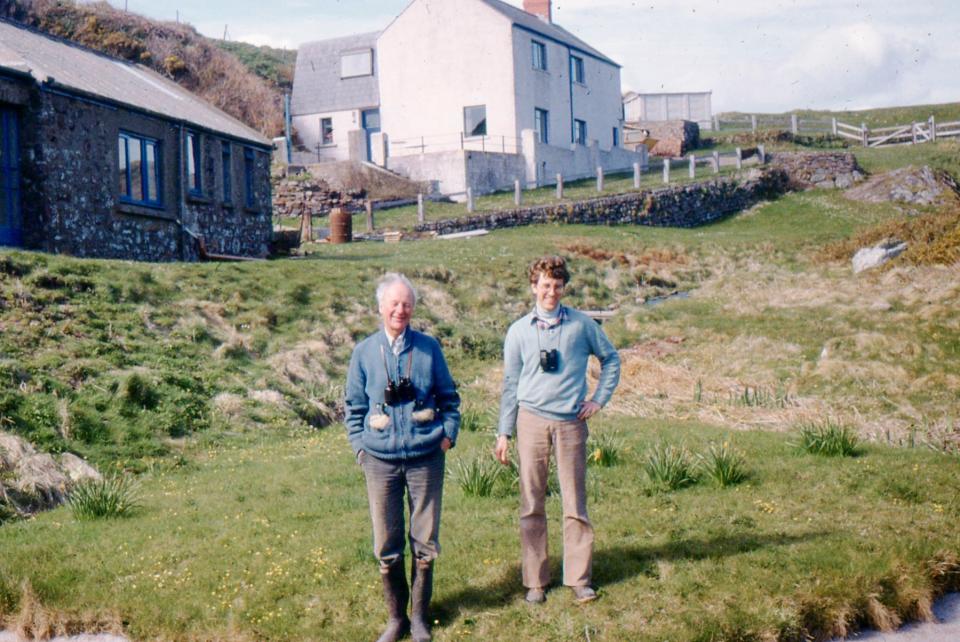

Dr Stephen Andrews is Principal of Wycliffe College and former Study Assistant to John Stott (1984-1986).