I am in the middle of reading St. Benedict’s Rule with my 30 students in the first year MDiv course at Wycliffe called, “Life Together: Living the Christian Faith in Community.” We have come to the fun part of this portion of the class. First, students read the Rule straight through and shared their impressions. Many are skeptical. It’s really old, written for monks and nuns (not evangelical Protestants) and it has way too much detail about everything from how to pray to how to wash the dishes. And then there is the low-hanging fruit: the comment about not laughing, some corporeal punishment and the authority of the abbot. But after this we begin to look at it more closely through secondary literature. We are reading portions of Esther de Wall’s classic, Seeking God and Rowan Williams’, The Way of St. Benedict.

This is the enjoyable part. My students are discovering that Benedict’s Rules still speaks today to living our faith in community. This is no surprise; after all it has stood the test of time, is a foundation of Western Christianity, and the basis of the new monasticism. But this year is different. We are all on Zoom, stuck in our homes or apartments, trying to juggle work, children, classes, frail parents, and friends, as well as uncertainty and growing polarization about the future. What we are discovering—all of us together—is that the Rule is a gift to us at just this time. There is something counterintuitive about this: St. Benedict compiled the Rule for those living physically together—within the enclosure of the monastery. Yet, this is a time during which many of the ways we normally gather as Christians, students, families, citizens, employees, and colleagues have been taken from us. How can this be that St. Benedict’s Rule is guidance and encouragement in these tough days?

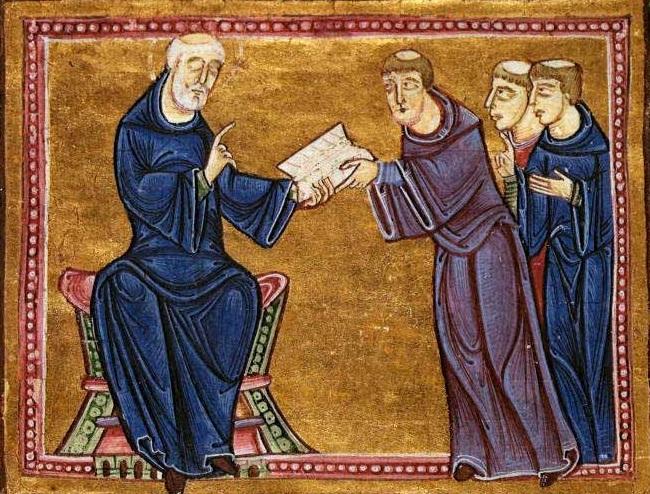

St. Benedict of Nursia (480-547 C.E.) compiled his Rule or rhythm for life together in Christ at a time when much of the world had lost its bearings. In the 5th century the Roman Empire had collapsed. Western Barbarians, who had seized control of much of its lands, dismembered what was left of it. Lost was not only the political unity enforced by the Roman Empire’s military. The unity of the Empire had been the foundation of the flourishing of much of what makes a civilization: trade, manufacturing, widespread secular literacy, the arts, science, agriculture. These too were eviscerated.

Into this uncertainty and fear St. Benedict laid out a rhythm for listening to and responding to Christ with the Gospels as the guide. Its gifts to us at this time of Covid are numerous. So many are suffering alone. We have been forced into the enclosures of our homes—perhaps similar to the monastery. Our daily rhythms, our plans for traveling, schooling, children, and work have not been eviscerated, but certainly have been flattened out.

We cannot escape the daily, the monotonous, those who are difficult, or even ourselves. And that is how it should be, according to St. Benedict. In the enclosures imposed on us by the spread of Covid—just here—St. Benedict encourages us to listen to and respond to Christ with the Gospels as our guide. Here are six gifts of the Rule from across the centuries.

- Stability, rooted in God’s stability with us, in the necessary foundation of holiness. Not going anywhere is a condition of reducing the Covid infection rate and saving lives. For St. Benedict stability, imposed or freely chosen, is the necessary foundation for holiness because we cannot run away from ourselves or others. Stability invites us to ask what are the necessary habits and disciplines which allow us to live stably with others? In our homes, congregations, and nations? Essential questions right now.

- God does not demand the heroic: At the heart of the Rule is this promise and call: each ordinary day is an opening to life with God and we are called to make each day captive to Christ. God does not demand the spectacular or the heroic. What we do in the most ordinary and monotonous day, with openness to God and those with whom we live, is where we meet God. During Covid just this—getting through our days with patience, kindness and hope—feels heroic to many. This is all God asks and everything God promises is received here.

- What we do with our hands, feet, and mouths matter. There is nothing abstract about St. Benedict’s Rule. No grand statements about God’s love or justice. No speculative Christology. Seventy-three short chapters contain instructions on how to organize work, study, and prayer, welcome guests, distribute clothing, keep silent, avoid grumbling, and care for the goods of the monastery. St. Benedict describes holiness as a set of habits, which practiced over time, become like well-worn gardening tools in a gardener’s hands (chapter 4). This prosaic path to holiness is ours during Covid: from who makes the bed to who leads grace at mealtime.

- A rhythm to our day is absolutely essential. One of the losses at this time is the rhythm that shaped our days. Days have flattened out into an undifferentiated continuum. St. Benedict knows that we need help in imposing both an internal and external order to our days if they are to be an opening to God. Prayer, study, and work, ora et labora, is the heart of the Rule. Work is dropped when it is time to pray. Prayer is the central work of the Christian. This has not changed in Covid; but we need to impose a rhythm ourselves: of prayer, work, and study, sleep, meals, physical activity. We need accountability to do so. Livestream Morning Prayer at Wycliffe is a lifeline and invitation to begin our days of ora et labora with common prayer.

- Our holiness, found in Christ’s, is inescapably bound to our relationship with others. Williams writes, “Each member of the community regards relation with the others as the material of their own sanctification, so that it is impossible to see the other as a necessary menace”(Loc 236,7). There is perhaps no more counter-cultural claim than this as nationalism and divisions increase. In our longing for justice the Rule tells us that dismissing and canceling others is not to be the Christian’s way. Whether we are living with difficult family members, roommates or within national divisions. Or spend time blogging and tweeting. Call no one a menace: not only are they not going away (which we may think would solve everything) but they are essential to our holiness. The question the Rule is shaped by is: how do we learn to live, listen, and mend relationships with the others instead of pushing them away?

- Work is essential for everyone and all work is holy. All tools in the monastery are treated with equal care (ch. 31, 32). From the vessels in the Chapel to the trowels in the garden shed and plates in the kitchen. All are to be treated as sacred vessels of the altar, St. Benedict writes (ch. 31). Participation is at the core of the place of work in the Rule. Everyone works in the monastery in work appropriate to age and ability (ch. 48). But no work is deemed more important or holy. All of it is participation in the creation of an environment where humans grow and thrive. The Rule is an alternative vision of work to meritocracy and a gig economy. Economies will begin the difficult work of recovering after Covid. Here the Rule moves out of the monastery and our homes to offer its gifts to nations and societies, much as it did when first written. Work must be for everyone. Everyone needs to work as participation in our restored humanity. For the sake of the common good—our life together—which includes the land.

St. Benedict’s Rule, compiled when much of the world has lost its bearings, speaks a living word at this time of disorientation. The Rule begins with a single imperative: listen. God calls us to listen—and create external and internal rhythms for doing just that. Listen to the living voice of Jesus Christ whose Word and voice is very near. Right where we find ourselves today.