Twenty-five-year-old noblewoman Anne Askew (1521–1546) was accused of heresy, arrested, interrogated at least twice, tortured on the rack, and burned alive at the stake. Her account of her examinations was published together with the comments of exiled reformer and historian John Bale (1495–1563) as The first examinacyon (November 1546) and The Lattre examinacyon of Anne Askew (January 1547).

Askew’s journey toward death began during a trip to Lincoln Cathedral where, for six days, she read (and likely commented on) the English Bible that was chained to the pulpit. Askew was accused of defying the Act for the Advancement of True Religion (1542–1543) which, among other things, restricted gentle and noble women like Askew to reading and interpreting Scripture only in the privacy of their own homes. This Act also declared that if anyone should “publishe preache teach saye affirme declare dispute argue or hold any opinion” other than transubstantiation they would be “demed and adjudged” to be a heretic and suffer the “paynes of death by waye of burninge.”

The record of Askew’s examinations reveals her faith, her impressive knowledge and approach to reading and interpreting Scripture, and her theology. Scholars have identified more than fifty quotations and allusions to Scripture in her account of the proceedings. Most of her citations are drawn from Matthew, Luke, John, Acts, and Paul’s writings—especially his Corinthian letters—although she is clearly familiar with both Old and New Testaments. An example of her expertise and audacity appears in her answer to the chancellor who attempted to get her to unveil her position regarding the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Instead of articulating her anti-Catholic views, Askew side-stepped the question and suggested that the chancellor himself was unclear about his stance. Paraphrasing Elijah’s question to God’s people in 1 Kings 18:21, she asked, “How long halt ye between two opinions?” She then impudently instructed her examiner as to where he could find the biblical verse she had referenced. Having had enough of her “teaching,” banter, insolence, and what he called Askew’s “parroting” of Scripture, the exasperated chancellor ended this part of his examination of Askew.

When the learned theologian, Doctor Standish, asked Askew to explain her understanding of one of Paul’s teachings, she drew on traditional applications of Paul’s teachings about the role of women (1 Tim 2:12; 1 Cor 14:34–36) together with the authority of Scripture itself. Tongue in check, she replied: “It was against saynt Paules lernyge, that I beynge a woman, should interprete the scriptures, specially where so smanye wyse lenerd men were.” When another of her interrogators asked her why she had so few words, she countered, “God hath given me the gift of knowledge, but not of utterance [1 Cor 12:8]. And Salomon sayth, that a woman of few words is a gift of God” [Pro 17:27–28; 31:26].

Askew penned the prologue to the account of her second examination after she was sure of the trial’s outcome. Setting aside the shield of silence and openly confessing her faith, she set out her understanding of communion, acting on her belief that Paul’s silencing strictures applied only to women preaching from a pulpit.

The breade and the wyne were left us, for a sacramentall communyon, or a mutuall pertycypacyon of the inestymable benefyghtes of hys most precyouse deathe and bloud shedynge. And that we shuld in the ende therof, be thankefull togyther for that most necessarye grace of our redempcyon. For in the closynge up therof, [Jesus] sayd thus. Thys do ye, in remembraunce of me. Yea, so oft as ye shall eate it of drynke it. Luce 22. and 1 Corinth. 11.

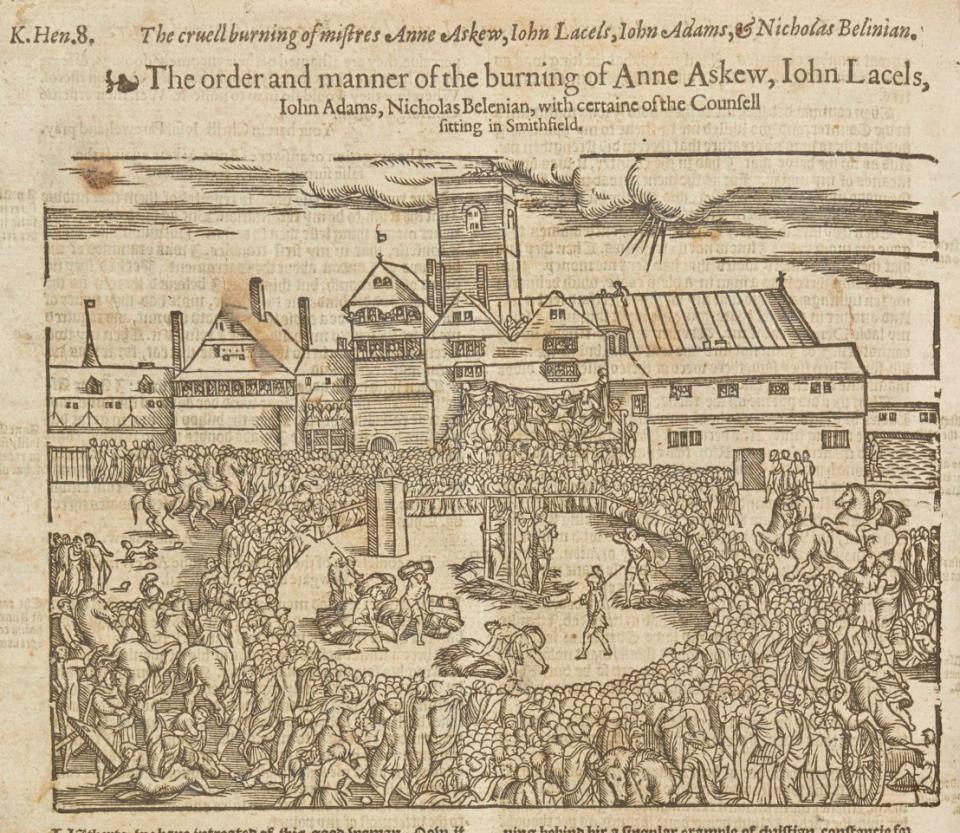

When her examinations concluded, Askew was brutally tortured on the rack. Her limbs were dislocated by her examiners as they tried unsuccessfully to get her to reveal the names of other women associated with the reformed-minded Queen Katharine Parr. In one of her last entries, written in Newgate prison, Askew shared—“in all my lyfe afore, was I never in soch payne.” Her body was so broken that she had to be carried to the stake on a chair. In her final confession, she compared the spiritual blindness of her interrogators to that of the Israelites who could not see the glory on Moses’ face because it was veiled; as Paul wrote in 2 Cor 3, she believed that “the same vayle remayneth to thys daye.” She looked forward in hope for the day that God would lift the veil and let “these blynde men se” what Paul described and what she continued to experience as the glory of the Lord.

Reading Scripture was a dangerous activity for Anne Askew, yet it also gave her the courage to resolutely hold onto her faith and the hope of everlasting life. Anne Askew’s example continues to inspire Christians today to hold fast to the truth of the gospel. Like Askew, we should “read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest [the Scriptures], so that by the “patience and the comfort of God’s holy Word, we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life, which thou hast given us in our Saviour Jesus Christ.” [The Collect for the Second Sunday of Advent in England’s Book of Common Prayer]