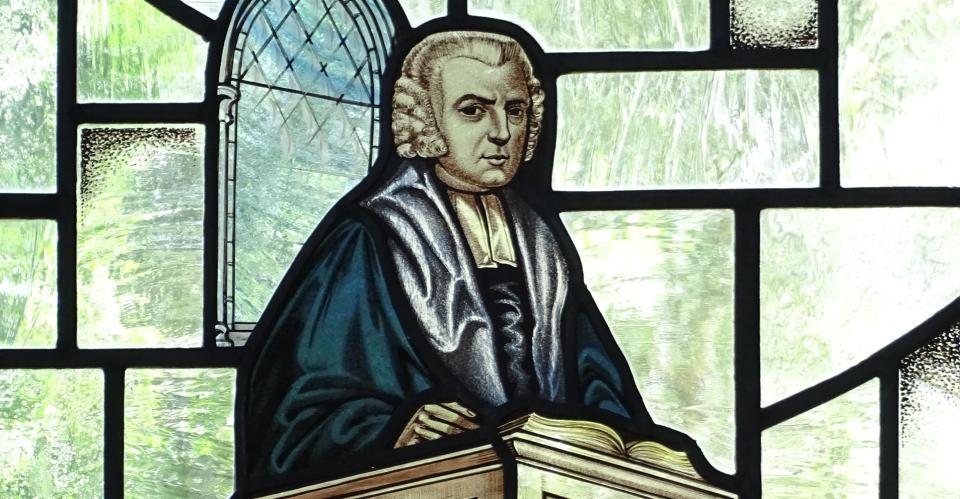

You may be familiar with Rev. John Newton (1725-1807) as the author of the famous hymn, Amazing Grace. What you may not know is that he came to have an important ministry as a spiritual director, primarily through letter writing. Many people wrote to him for advice and he replied giving counsel and direction on a variety of matters, such as grace, temptation, evil, Christian character, vanity, sin, and sorrow.

He composed one of his letters, “Marks of a Call to the Ministry,” in response to someone seeking advice on discerning a call to ministry. At the outset of the letter, Newton provided a frank personal admission that “my first desires towards the ministry were attended with great uncertainties and difficulties, and the perplexity of my own mind was heightened by the various and opposite judgments of my friends.” He admitted that he had long struggled about what was or was not a proper call to ministry. He then offered his correspondent three pieces of advice that are still pertinent today.

“A warm and earnest desire”

Firstly, Newton identified “A warm and earnest desire to be employed in this service” as foundational and prescriptive to a call to ministry. If the Spirit has called a person to ministry, then that person will come to prefer ministry to the material attractions of the world, despite a sense of inadequacy, and in this will be sustained by humility. For Newton, a good test in this regard was a prospective minister’s attitude to preaching. If, on the one hand, we have a strong desire to preach when we are “most fervent in our most lively and spiritual frames, and when we are most laid in the dust before the Lord,” then this attitude is commendable. However, if a person is strongly desirous of preaching to others but finds “little hungering and thirsting after grace in his own soul,” then the desire derives from a selfish motive.

“Some competent sufficiency”

Secondly, Newton urged his correspondent to look for the presence in himself of “some competent sufficiency as to gifts, knowledge, and utterance.” His rationale here was that if God commissions a person to teach others, then God will provide the means. This, in Newton’s mind, distinguished the intended minister from the lay Christian. The appearance of such gifts, however, may not be immediate but gradual and “in due season.” He makes clear that possession of such gifts is essential for performing the duties of ministry, but he equally insists that they are “not necessary as pre-requisites to warrant our desires after it.” On the whole, Newton felt that aspirants to the ministry need not feel too concerned whether at the outset they possessed the requisite gifts. It was more important that their desire and willingness was strong, specifically a willingness in waiting on the Lord in “prayer and diligence” as the means of attaining the necessary gifts.

Providence and circumstances

Thirdly, Newton recommends that providence and circumstances should be looked to as determinative as to when and where one should enter the church. Until these come into play, the way ahead will not always be as clear as one expects. At the same time, one should not be over-hasty in interpreting circumstances. The important point to remember is that if God wants you in ministry, then God has already appointed the time and place when that will happen: “If you had the talents of an angel, you could do no good with them till his hour is come, and till he leads you to the people whom he has determined to bless by your means.” Cautioning against over haste, Newton cites the fact that it took five years of waiting before his own call was realized. He cautioned his correspondent, therefore, to take his time and advised him to “be content with being a learner in the school of Christ for some years.” During this time of waiting, he advised against engaging in “disputes” —by which he meant theological controversies, which at the time, involved Arminians and Calvinists—if they were unlikely to prove beneficial or useful. (He counselled on such disputes: “They tend to eat out the life and savour of religion, and to make the soul lean and dry.”) Additionally, the time of waiting could be filled by engaging in private study, being exposed to “Gospel preaching,” and being among a “lively people.”

Humility

From an initial admission on his own struggle, unworthiness and uncertainty, Newton counsels humility in light of the work of the Spirit (a test of which is one’s attitude to preaching), a discernment of gifts (but not being overly concerned about their immediate presence in preference to waiting in prayer on the Lord), and not being over-hasty in wanting to precipitate events but to use one’s time of waiting wisely.

Setting aside some old-fashioned language, Newton’s explication of the call to ministry is a thoughtful and incisive dissection of a person’s motives, the value of which can apply to those contemplating the call today.

***

Thomas Power is Adjunct Professor of Church History and Theological Librarian at Wycliffe College. During the Winter 2020 academic term, he will teach a survey course on, "The Protestant Reformation."