Some of us are fortunate to have one or more teachers in our lives whose influence on us is significant and memorable. In this blog post, Wycliffe Professor of Systematic Theology, Joseph Mangina writes about one of his own such teachers, professor George A. Lindbeck.

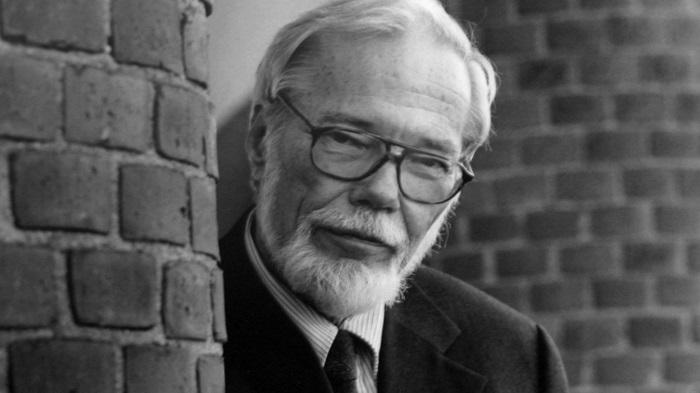

While a student at Yale Divinity School in the late 1970’s, I took a required course on the history of medieval and Reformation theology with a professor named George Lindbeck. With his horn-rimmed glasses, salt and pepper beard, and rumpled appearance, Dr. Lindbeck looked every inch the ivory-tower academic. I recall that he would take long (I mean, really long) pauses during his lectures, staring out the window as if the phrase he was looking for might be floating somewhere in the clouds. Though the lectures meandered a bit, they were also fascinating and rich in insight. Lindbeck had a gift for making figures like Augustine, Aquinas, and Luther come alive as readers of Scripture and servants of Christ’s holy catholic church.

George Lindbeck died this past January 8, at the age of 94. What I did not know as an M.Div student was that Lindbeck had already had a distinguished career as a historian of doctrine and ecumenical theologian. Raised in China, of Lutheran missionary parents, he returned to the United States just before the Second World War to study at Gustavus Adolphus College and, later, Yale Divinity School. He also spent time in Toronto at the Pontifical Institute for Medieval Studies, then under the leadership of Étienne Gilson. In part because of his knowledge of medieval philosophy, he got caught up in the early stirrings of Roman Catholic-Protestant ecumenical dialogue. When Pope John XXIII convened a church-wide council early in his papacy, Lindbeck was called upon to serve as an official Lutheran observer at what would become known as “Vatican II.” Lindbeck and his family actually lived in Rome for most of the period between 1962 and 1964, giving him a unique perspective into not just the theology but the politics and personalities of the Council. He would later write that his experience at Vatican II was the most important event of his life. During and after the Council Lindbeck wrote scores of papers and articles in the service of Christian unity, serving as co-chair of the International Lutheran-Roman Catholic Dialogue Commission, and laying the early groundwork for the Joint Declaration on Justification by Faith (1999). If he had done nothing else besides this ecumenical work he would have an assured place in theological history.

But he did much more. Part of the point of Christian unity, after all, is that it should help strengthen the church in her vocation of witness to the world. But by the 1970’s, it was becoming increasingly clear to Lindbeck (as also to other ecumenical pioneers, such as Lesslie Newbigin) that the promise of ecumenism was not being fulfilled. The churches of the West were converging, all right—in their capitulation to the mores and assumptions of the surrounding culture. Lindbeck began a second career, as it were, reflecting on what it might mean for the church to be a “perhaps repugnant minority” in a world after Christendom. He became very interested in the language, social practices, and habits of reading Scripture that form Christians in their faith. This led to his best-known book, The Nature of Doctrine: Religion and Theology in a Postliberal Age (1984). It should be noted that Lindbeck’s early experience of Christian mission played an important role in his thinking: growing up in China, he never assumed that the church should be other than a mission outpost among the nations. As he pondered the biblical story more deeply, he came more and more convinced of the church’s profound solidarity with the Jews, the original pilgrim people of God. Two of Wycliffe’s current doctoral students, Joshua Martin and Shaun Brown, are in fact exploring the Lindbeckian theme of the “church as Israel” in their respective dissertations.

After finishing my M.Div., I was lucky to be able to continue on at Yale to do doctoral studies under George Lindbeck; among my fellow students were Ephraim Radner and George Sumner, former Principal of Wycliffe College. I always found George Lindbeck to be the kindest and most generous of teachers. If students occasionally catch me gazing out the window to find just the right words, they will know where I developed that tic.