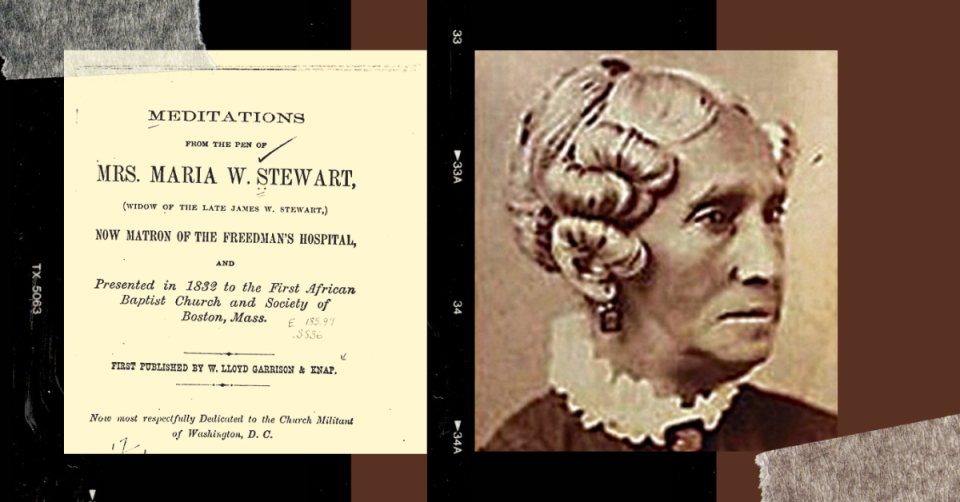

Early African American women dared to preach and call for personal and societal change. These heroes of faith inspire us and need to be remembered. We stand on their shoulders as we continue to battle over questions of gender, race, and biblical interpretation. African American abolitionist, moral reformer, and educator Maria W. Stewart (1803-1879) is one of those heroes. Stewart dared to heed God’s voice in calling for individual and collective transformation. Her inspiring Meditations from the Pen of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart is found on Google books.

Scripture captured her mind and imagination

Maria W. Stewart was orphaned at age five and raised in a white minister’s home in Hartford, Connecticut where she worked as a domestic servant until she was fifteen. Even as a child, Scripture captured Stewart’s mind and imagination. According to her Meditations, while she toiled with her hands for “daily sustenance, [her] heart . . . most generally meditat[ed] upon [the Bible’s] divine truths” (p.2). In 1826, she married James Stewart, a biracial Episcopalian Navy veteran and successful Boston businessman. They were married by the pastor of the Baptist African Meeting House, a center for educational reform and abolition that provided many free African Americans with a spiritual home where they could worship without discrimination. This community of ardent abolitionists was her main support during a series of losses: her husband died in 1829, she was defrauded of her substantial inheritance, and her mentor, leading abolitionist David Walker, died in 1830. She writes that a conversion experience in 1830 gave her a new sense of belonging and purpose as “in imagination, I found myself sitting at the feet of Jesus, clothed in my right mind” (p. 74). She felt called “to devote the remainder of my days to piety and virtue, and now possess the spirit of independence that, were I called upon, I would willingly sacrifice my life for the cause of God and my brethren” (p. iv).

For the next three years, Stewart preached to African Americans with her pen and from behind lecterns. She spoke words of judgment and hope, using the kind of moral figuralism that was a staple of Protestant exegesis in America since the Puritans. Some even called her “America’s preeminent Black Woman Jeremiah” (p. 303).

Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879) published Stewart’s first essay “Religion and the Pure Principles of Morality, the Sure Foundations on Which We Must Build” in his newspaper The Liberator in 1831. Four years later he published Productions of Mrs. Maria W. Stewart, a collection of Stewart’s Boston lectures, including her farewell address of September 21, 1833 and her religious meditations and prayers. These writings, which were republished again in 1876, showcase her “figural” approach to interpreting Scripture. Stewart believed that the story of God in Scripture was not locked into the past in its depictions of Israel in Egypt and Babylon, but described by analogy, association, and metaphor the story of Africa’s enslaved and freeborn daughters living in America. As God’s mouthpiece, Stewart called in her Meditations for an end to African Americans’ experience of being “an hissing and a reproach among the nations” (Jer 29:18). She lamented the “wretched miserable state” of African Americans using the words of Jeremiah: “O that my head were waters and mine eyes a fountain of tears, that I might weep day and night for the transgressions of the daughters of my people” (Jer 9:1). She declared to the exiles that God had a message for them: “Truly, my heart’s desire and prayer is [Rom 10:1: that “Israel might be saved”] that Ethiopia might stretch forth her hands unto God [Ps 68:31: “Princes shall come out of Egypt; Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God.”]. But we have a great work to do [Neh 6:3]. Never; no, never will the chains of slavery and ignorance burst till we become united as one and cultivate among ourselves the pure principles of piety, morality, and virtue” (p. 24–25).

Drawing her authority from the apostle Paul, Stewart declared: “I speak as one that must give an account at the awful bar of God [Rom 14:10-12: “every one of us shall give account of himself to God”]; I speak as a dying mortal, to dying mortals [2 Cor 4:11].Stewart’s call, “O ye daughters of Africa, awake! Awake! Arise!” echoes God’s calls to the daughters of Zion to hear the battle cry and to awake [Judg 5:12; Isa 51:9, 17; 52:1]. Her call is not to arms but to moral and spiritual change: “What foundation have ye laid for generations yet unborn?” (p. 24–25).

A message of divine judgment

Stewart’s message of divine judgment for the African Americans’ oppressors was both evangelical and political. In one of her meditations, she blended Jesus’s teaching about gaining the whole world and losing one’s own soul (Mark 8:34-38) and Jesus’s parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). Stewart implied that rich and spiritually-hardened Euro-Americans like the rich man in Jesus’s teachings would end up in the eternal fires of hell, where Father Abraham would refuse to send Lazarus [oppressed African Americans] to serve them even drops of water (Luke 16:19-31): “And what gratification will it be to you, my friends, to think that you have been able to be decked in fine linen and purple, and to fare sumptuously every day, if you are not decked in the pure robes of Christ’s righteousness? And, friends, what are they in that awful moment, if the eternal God is not your friend and portion?” (p. 47).

Stewart was similarly critical of African American men and community leaders: “When I cast my eyes on the long list of illustrious names that are enrolled on the bright annals of fame among the whites, I turn my eyes within and ask my thoughts, ‘Where are the names of our illustrious ones?’ It must certainly have been for the want of energy on the part of free people of color that they have been long willing to bear the yoke of oppression. It must have been the want of ambition and force that has given the whites occasion to say that our natural abilities are not as good, and our capacities by nature inferior to theirs.” (p. 66).

This lecture at the African Masonic Hall on February 27, 1833 was not well received and precipitated the end of her public ministry in Boston.

Stewart moved to Brooklyn, NY to pursue further education. As Marilyn Richardson notes in Maria W. Stewart, America’s First Black Woman Political Writer, she joined a women’s literary society and continued to advocate for the rights of African Americans, attending the first Women’s Anti-Slavery Convention of 1837. In 1852, Stewart moved to Baltimore, and then Washington, DC in 1859. As she pursued her vision of improved education for African American children, she struggled to support herself. A number of Christian denominations established schools for African American children and paid their teachers, but her “white folks’ church” refused to support these efforts. Still Stewart remained a loyal Episcopalian: “Well, before I will give up my religious sentiments for dollars and cents I will beg my bread from door to door.” Without the financial support of her church, Richardson writes, Stewart “did almost beg her bread.”

“Holy indignation”

In her writings about her sufferings during the period of the American Civil War, Stewart continued to embody Scripture. She compared her experience as one of “a handfull of . . . poor lone colored women followers of the cross” refused communion in the Episcopal Church in Washington to that of “the outcasts of the house of Israel.” Although she was “filled with holy indignation,” she “clung to the church” (Meditations, p. 22).

Stewart had a vision of an Episcopal Churchwhere African Americans could worship without the indignities of being forced to sit in remote corners of the church, receiving communion after the whites or not at all, limited access to baptisms, marriages, and burials in the church, and segregated Sunday school classes. After two years of planning, the first African American congregation in Washington DC, St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, was established in 1867. Stewart expressed her joy: “. . . by grace I overcame; and to-day am one of those that John saw in a vision on the Isle of Patmos having harps in their hands [Rev 15:2]. I have suffered martyrdom for the church in one sense; and rejoice that I now feel that I have a home not only in the Protestant Episcopal Church, but in the Holy Church Catholic throughout the world (Meditations, p. 22).

Stewart used an approach to reading Scripture she had learned in her evangelical tradition and intuited through her African American experiences. She inhabited the Scriptures she knew so well and loved. Scripture authorized her to speak and to act; her bold moral and prophetic preaching called Africa’s sons and daughters and their oppressors to radical moral and political transformation. Her preaching became more nuanced over time, but her figural approach did not change. She continued to make Scripture’s words her own. Its words, characters, and events carried far deeper significance than their literal sense. They spoke into the present and the future.

Stewart is an African American woman who mattered in the nineteenth century, and she matters today. We can learn from her lively engagement with Scripture, which continues to speak words of comfort and judgment into a world that desperately needs to encounter the God who gave Stewart both vision and hope. The American Episcopal Church continues to recognize Maria Stewart as a prophetic witness in their liturgical calendar.