A Commentary on the Address of the Bishop of Exeter to the American House of Bishops"

by the Rev. Dr. Andrew Goddard, Anglican Communion Institute Fellow

The content of the address of the Bishop of Exeter to ECUSA’s House of Bishops would have made it highly significant in its own right. The fact that he delivered it as the representative of the Archbishop of Canterbury ‘who”, as Bp. Langrish says, “specifically asked me to bring you this message and assure you of his own prayers’, makes it perhaps the most important and illuminating perspective since the Dromantine Communiqué from the Primates on the current and future state of the Anglican Communion and the decisions facing ECUSA in just under three months.

What follows offers an interpretation of its main content and significance. It is designed especially for those in ECUSA, as they approach General Convention and as they prepare to make decisions which will have a major effect not only on their own church but on the Church of England, the wider Anglican Communion and the whole church catholic. While the full force of the communication can only be gained by careful reading and re-reading of the message brought to ECUSA’s bishops, its key central themes fall into four broad categories: an analysis and critique of the appeal to context in theology, a reaction to the work of ECUSA’s Commission on Windsor, an interpretation of the dynamics within the Communion and finally the choices now facing ECUSA.

Christian contextual theology: A critique of ECUSA’s theological method

In bringing greetings, giving thanks for hospitality received, and introducing himself, the Bishop of Exeter also put himself in context – as he put it, his lack of American experience, coupled with his knowledge of the wider Communion. He also – signalling an important sub-text of his presentation – rather bluntly (especially for an English bishop used to reserved understatement) asks whether Americans are really self-aware and fully understand their own context: ‘I do wonder to what extent Americans recognise and understand just how great this dominance and influence [of American culture] really is’. He thus quickly acknowledges the fact that none of us come at any issue with a God’s-eye perspective but rather with ‘a particular set of filters, and contexts’ through which we view issues.

This acceptance of our locatedness implicitly recognises the need for dialogue and humility, something Bishop Langrish relates to the Presiding Bishop’s question (apparently raised earlier in the meeting) about why there is so much suspicion of talking about ‘context’ in many circles. The emphasis on ‘context’ is, of course, a regular theme in Frank Griswold’s responses to the recent crises engendered by the last ECUSA General Convention and his various attempts to explain and defend what has taken place. To cite just three examples:

1. In his letter to the Lambeth Commission Griswold wrote, “I remember vividly when I visited the Church inNigeria and was asked if I was coming to tell them they must ordain women. I told them I firmly believed that is a decision they will have to make within the reality of their own context. There is not one right way. Immediately, there was relief on the part of the bishops. This raises the very important notion of context, to which I alluded earlier. We must ask: are our understandings and applications of the gospel conditioned by the historical and cultural circumstances in which we live our lives and seek to articulate our faithful discipleship? I believe the answer is yes. As one primate expressed it ‘the Holy Spirit can do different things in different places.’ When I think of a way forward, the first thing I think of is the need to be respectful of one another’s contexts, to trust one another, and to honor the fact that we are each trying to be faithful in very different circumstances. I pray we can acknowledge to one another that we are each trying, with God’s help, to articulate and live the gospel within the givenness of our own context”.

2. In his initial response to Windsor – “As Anglicans we interpret and live the gospel in multiple contexts, and the circumstances of our lives can lead us to widely divergent understandings and points of view…It is important to note here that in the Episcopal Church we are seeking to live the gospel in a society where homosexuality is openly discussed and increasingly acknowledged in all areas of our public life.”

3. In his recent interview on the listening process – “I think listening is particularly important at this moment in the life of the Anglican Communion because we live across the Communion in very different contexts and are shaped and molded by very different historical, political, and ecclesial realities.”

In reflecting on this theme of ‘context’ Bishop Langrish laid the groundwork for his later comments and offered some crucial methodological critiques of much official ECUSA theology.

Firstly he warned of ‘context’ being ‘used as a trump card played on behalf of one belonging over another’. Instead, he spoke of ‘unbelongings’ with that word’s sense of ‘rootedness and detachment’. The message in this is clear, particularly when the warning about trump cards is followed by this statement: “if that context is an imperial or superpower context then the suspicion of it being played as the card that will trump all other contexts does become very considerable”. In short, a number of American justifications for disregarding Lambeth I.10 have appealed to the American context, but this on its own is not a valid method of contextual theology in the Christian church. In fact, it may amount to, or certainly be experienced as, a form of oppression.

Secondly, by use of an analogy with a conference on the Middle East, Langrish makes his point clear about American conduct within the Communion and how the American pattern of behavior and positive talk of ‘engagement’ as an expression of their commitment to communion is heard: many are “fearful that in any engagement…[they] would be swamped or even obliterated by another context, especially one seen to be gaining in hegemony”. That is, one cannot speak of engagement and ‘having everyone at the same dialogical table’ simply by talking of ‘context’ unless it is coupled with ‘a sense of belonging and a willingness to face unbelonging’. The implications of this in the face of American ecclesial unilateralism and the demands of the Windsor Report are clear.

Thirdly, Langrish then offered a subtle but powerful critique of an approach to theological diversity and development that privileges local context. Without rejecting the importance of such local context, he was emphatic that as Christians we all need to be ‘set within a bigger context than any single cultural or political context can provide’. Part of what that means is that we cannot appear to be duplicitous or ambiguous in our communication – ‘we do need to find ways of sending clear signals to one another’. Nor can we rush into action. We must rather ‘make time’. Above all, we need to be self-aware. We cannot simply defend our actions as necessary in our context which is so different from that of others: we must ‘learn to step back and to consider where in Christ there is a bigger context, some meta-narrative, that encompasses them all’.

Fourthly, Langrish illustrates the suspicion with which appeals to context must be judged by reference to a Nigerian claim that those who brought them the Bible no longer believe it. Although confessing that mission to Africa was shaped by its Western context, he nevertheless notes the inevitability of suspicion or ‘something like a tectonic change or betrayal’ when ‘the presenting culture, or context, seems to have itself undergone a paradigmatic shift, particularly where this occurs without engagement and dialogue (all of which takes time)’. The message is here is forthright: American Episcopalians need to realise just how far and how rapidly and how unilaterally and imperiously – in the eyes of much of the rest of the Communion – they have moved from the gospel that other parts of the Communion originally received from them.

Finally, least this all be too subtle, his fifth critique of much contextual theology is straightfoward: it is much easier to see and fear another’s context and highlight how they are shaped by it ‘than it is to step back and examine our own’. So although it may seem obvious to American revisionists that the churches of the Global South are taking their stance because of the threat of Islam, nonetheless ‘perhaps we need to reflect on the contextual pressures on us as we read, interpret and defend the Bible in the context of postmodernist culture in which suspicion of metanarrative appears to have become the norm’.

Very carefully, rather subtly, ECUSA liberals here have their critique and method applied to themselves and their own ‘context’. They can deconstruct African opposition to their actions as an inability to understand their American context and as something which is simply shaped by the African context. But in fact, their whole method of contextual theology is itself largely a reflection of their American context and shaped by an imperial American mindset with its culture of postmodern relativism. The problem is that, arising from, and shaped by such a context, this approach which is so dominant in ECUSA is – despite all its protestations – incapable of genuine dialogue and engagement. It has been developed without any such process and it has lost sight of the fundamental – catholic and biblical - Christian identity and context of life in Christ.

Having opened with such a penetrating analysis of the underlying theological method regularly used to justify ECUSA’s recent actions, the specific discussion that follows in relation to the Windsor Report should come as no surprise. The Bishop of Exeter has, in effect, signalled that the actions of GC 2003 (and the as yet less than full embracing of the Windsor Report) are simply symptoms of a much more serious cultural and theological disease. ECUSA must treat that disease with the medicine of life in communion offered by the Windsor Report. But the danger is that they will either not realise the nature of the disease or refuse the only remedy on offer.

The Work of the ECUSA Commission on Windsor

After a short pause to speak very positively of his experiences in the House (which provide ‘a context that is particularly helpful for responding to the work of the special commission’) and of the care and seriousness of the Commission’s work, Bishop Langrish offered his thoughts on different aspects of that work-in-progress and their possible consequences.

He first stressed to the American bishops the importance that ‘your intention and desire is to do not just what is expedient, but what is right…Mere expediency will serve no one well’. It is perhaps because so many fear a ‘fudge’ from General Convention that the Archbishop of Canterbury’s representative was again remarkably frank in stating that, although a principled response of compliance or non-compliance will ‘have consequences and almost certainly very profound ones’, the seriousness of what is at stake cannot be underestimated and the task is clear: ‘discerning the right, the divine word for now’.

Noting that there was much to encourage in the Commission’s work – especially what appears a most serious engagement and proposal in relation to the proposed covenant – the bishop was also able to be honest enough to name the remaining problems. Using language obviously encouraged in the HoB’s discussion he made crystal clear that there are also elements in the proposed report which ‘give me pause for concern’ and ‘real anxieties’. Two areas are particularly highlighted as needing much more serious work.

Consecrations to the episcopate

Windsor clearly called for ‘a moratorium on the election and consent to the consecration of any candidate to the episcopate who is living in a same gender union until some new consensus in the Anglican Communion emerges’ (para 134). However, the ECUSA Commission – apparently based on a report on its work to the House -- is simply asking General Convention to commit to ‘extreme caution’ on elections and consecrations of same-sex-partnered bishops. The problem here is ‘ambiguity of language’ and the ‘subjectivity of what is being asked for’, two hallmarks that some may find unsurprising in official ECUSA responses to the Communion.

The Bishop proceeds to define precisely the difficult features of the New Hampshire consent and consecration (and hence any similar future consecration). These are two-fold in that such actions amount to:

‘consecrating a Bishop – presumably with intent to create a bishop for the church catholic – without seeking the assent of that wider church catholic (and this is about more than consultation)’

‘ordaining to the episcopate someone (and I make a general rather than a personal point here) who was in a relationship not liturgically sanctioned by the church, and to that extent at least irregular’

It is these two features of all such elections whether in New Hampshire, California, Newark or anywhere else which in turn cause a double problem that is again clearly and unambiguously stated. The problems are:

‘the relationship between ordained representative ministry and relationships that are irregular and do not reflect the stated discipline of the church’

‘the appearance of having in effect taken that relationship decision, without wider agreement and by creating a fact on the ground’.

It is in the light of these features and these problems that the question of any such future consecrations must be assessed. That is why ‘extreme caution’ rather than ‘refraining’ from such future consecrations is – despite its nod towards Windsor and the wider Communion – a wholly unsatisfactory wording. It amounts to a failure to understand the real nature of the problem, confirms an inability to critique one’s context, and represents a failure to embrace the vision of communion set out in Windsor. Indeed, it is such a vague and subjective commitment that, far from resolving the current crisis, it only ‘injects further difficulty into the life of the Communion’ and effectively constitutes a ‘challenge to the Communion’.

This analysis of such consecrations also suggests that the more fundamental challenge is that of ‘dealing with the issue of same-sex blessings first’ even though ‘this would almost certainly cause even greater problems for the Communion’. This is another easily missed but crucial point in the address. It is particularly highlighted in the way in which Bishop Langrish has defined the features and problems of Gene Robinson’s consecration: unless and until the church has an agreed vision of a godly same-sex partnership one cannot legitimately ordain or consecrate people as bishops in the church who are in same-sex partnerships. That is why the ECUSA Commission’s apparent willingness to accept the Windsor moratorium on authorised same-sex blessings does not cohere with their refusal to effect a similar moratorium in relation to consecrations: one cannot logically refrain from blessing liturgically but only commit to ‘extreme caution’ in relation to consecration.

Regret and Repentance

Interspersed with his ‘pause for concern’ over future consecrations, Langrish briefly but precisely addresses another area of ‘mutual incomprehension’: the language of regret. He is clear that what is sought by Windsor (and the Communion) is not regret for pain caused nor regret for doing something one believes was right and beneficial. What is sought is rather – and here he refers to the important English Bishops’ response to Windsorthat well repays re-reading in the preparations for General Convention -- repentance. This is, crucially, not to be understood (as perhaps some calls have implied) ‘in punitive or scapegoating terms’. It is rather the ‘seeing of an action or behaviour in a new light; of new circumstances under God, understanding it afresh and changing behaviour accordingly, not out of fear but out of love’. And that form of repentance, of course, will require a certain ‘unbelonging’, a distancing from one’s natural context, both cultural and ecclesial. It needs ‘a bigger and more dynamic understanding of communion (as envisaged in The Windsor Report)’.

The Wider Communion and Windsor

After so sharply assessing both ECUSA’s theology and its possible response to Windsor, the Bishop of Exeter proceeded to put ECUSA’s own wrestlings in a wider Communion context. He makes patently clear that ECUSA at General Convention is under the microscope – the Church of England is ‘watching very closely’ – and that the decisions taken will have major implications: ‘for good or ill what you do will affect us, and that in itself will impact on the wider communion, as well as on the major ecumenical and interfaith conversations in which, as a Communion, we are engaged’. The stakes are that high.

It is, however, not only ECUSA that threatens the Communion. Langrish also, importantly, emphasised that Lambeth I.10 and Windsor raise ‘other issues requiring repentance and revisiting’ and ‘there are also decisions that will need to be faced and taken by others if we are to go forward in fellowship and faith’. Doubtless with elements of the Global South (and some conservatives in Northern provinces) in mind, he highlighted the need for full commitment to ‘a genuine listening and conversational process in which we all are willing to learn and be changed under the guidance of the Holy Spirit’ and ‘a proper tackling (by us all) of the question of cross-provincial interventions’. The latter must include – perhaps here with an allusion to DEPO which the English HOB (unlike Windsor) viewed rather critically – ‘making appropriate provision for those who in conscience cannot accept, or who doubt the wisdom of, decisions made by others…’.

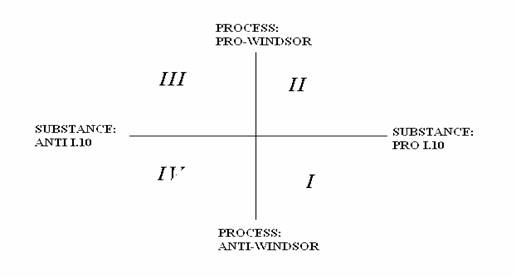

This recognition of wider threats to life in Communion then leads to a helpful analysis of the state of the Communion as ‘threatened by two intersecting fault-lines, each with its own totem’: same-sex relations (Lambeth I.10) and the nature and future of the Communion (Windsor/Dromantine). Here he identifies four groups which can perhaps be helpfully summarised by means of a diagrammatic representation of his analysis:

Group One (or at least the bottom right-hand corner of it) embraces ‘those who not only stand firmly by Lambeth I.10, but also see it as the litmus test of orthodoxy, and who are further opposed to, or have given up on, Windsor and all that it stands for’. Although he did not name who might fit this description, there was probably no need to do so for most members of the ECUSA HOB. Langrish was clear that ‘probably nothing that happens is going to satisfy them’.

Group Four includes ‘those who are so certain that Lambeth I.10 was wrong that they in effect see both Windsor and the Communion as a price that is simply to great to pay’. Here there are those who – as he later describes – believe they must be ‘prophetic’ and continue to follow the path of GC 2003 and disregardWindsor. One thinks here of such statements as those in the recent Guardian article of Marilyn McCord Adams.

However, ‘there will be those (probably the majority) who, while holding a variety of views on the issue of sexuality, would nevertheless to varying degrees also be committed to Windsor and its outworking in the Communion’s life’. These are groups Two and Three and ‘that would certainly be where to a very large extent, the English bishops will be found’. It is the cohesion, commitment and character of this coalition that is crucial.

The bishop then sketched out what that ground of living together as groups II and III might looks like, drawing on the experience of the CofE. He highlighted their recent report on sexuality (at a level of detail and scholarship found in none of ECUSA’s official publications over the last 30 years) and the features of holding this position. This form of life together must recongize:

· the ‘multifaceted and complex’ nature of questions of sexuality

· the inability to find ‘a quick resolution’

· the need to see issues of sexuality as not just issues of ‘justice and moral choice’ but of ‘the relationship between intimacy, sexuality and community, the connections between sexual behaviour and both human identity and human fulfilment, and the way in which, as part of our missiological imperative, we are to critique these things in society where sex and choice together make for such a dominant and formative force’

· the requirement that all the above ‘be held within a coherent exegetical framework’.

This commitment to Windsor means that, as a result, in the CofE House of Bishops, ‘despite the range of opinions there is an almost total intention to stand together, and with the rest of the Communion, in taking no precipitate action, as the listening and engagement go on’.

Having sketched this way of life in communion together represented by groups II and III the Archbishop’s representative then identified the fundamental question that is being put to ECUSA at GC 2006:

I suppose one of the major challenges for the Episcopal Church now has to do with whether there are enough of you to stand on broadly the same ground, holding a range of opinions on the issue of Lambeth I.10 but firm in carrying forward the Windsor vision of a strengthened and enabling communion life.

The Future of the Communion depends on Windsor and ECUSA’s response

Having framed the question in this way, Bishop Langrish then explains that the language so often used in the media and by angry people on both sides – that of being ‘pushed out’ or ‘consciously walking away’ - is unhelpful. This is because ‘no one can force another Province or Diocese either to go or to remain’. However, ‘equally, no Diocese or Province can enforce its own continued membership simply or largely on its own terms’. Instead of such insistence on one’s own agenda and the exclusion of those who disagree ‘there has to be engagement’. In short, and in contrast to some who so emphasise that our communion is in Christ or with the Trinity that they disregard the reality of ecclesial life and the disciplines and responsibilities of life in communion: ‘there is no communion without a shared vision of life in communion (at least that is how I understand Windsor)’. In other words, if ECUSA does not share Windsor’s vision of life in communion and refuses to put it into practice – by aligning herself with group IV rather than standing together committed to Windsor (whether in group II or group III) -- then this will mean there is no communion.

The implications of this refusal to fully embrace Windsor, irrespective of one’s views on Lambeth I.10, are then clearly stated in another crucial and revealing passage:

So it does seem to me, as I listen to those other parts of the Communion that I know best, that any further consecration of those in a same sex relationship; any authorisation of any person to undertake same sex blessings; any stated intention not to seriously engage with The Windsor Report -- will be read very widely as a declaration not to stay with the Communion as it is, or as the Windsor Report has articulated a vision, particularly in sections A and B, of how it wishes to be.

The evidence is, thankfully, that there is among ECUSA bishops ‘a desire for shared life in communion and ongoing engagement with others in just what this must involve’. The implications of that in terms of actions at GC are now clear. If that desire is not present or if the desire is not realised in the necessary actions of clear and unambiguous Windsor compliance then ‘there will be implications not just for the Anglican Communion, but for our international ecumenical and inter-faith dialogues too’.

Even if the desire bears fruit in actions, the Bishop of Exeter is clear that, though the right decisions will have been made and there will be positive implications, the simple truth is that ‘I doubt that these will be as immediately seen and felt. It is going to take time’.

However, some – the group IV (and perhaps the group I) identified above – may conclude that painful prophetic and disruptive action is what is now required. Whether or not they are true or false prophets only time will tell, but the consequences will likely have a long-term impact as ‘it is also clear that when real division…has occurred it has taken centuries for the break to be healed’. For those weighing whether to join the CofE HOB in groups II and III or to realign with group I or group IV, ‘a key issue of discernment is currently about the relationship between the perceived integrity of the Communion’s wider life and the prophetic imagination that a particular mission context might involve’.

In conclusion, Bishop Langrish sketches two features that will mark the Communion should ECUSA embrace Windsor and the Communion thus be preserved through the current crisis. First, its bishops need to ‘re-evaluate and rediscover our apostolic role within the body of Christ’. This is expressed in being ‘charged with the primary responsibility for articulating the faith and making new members of the Body of Christ’: a teaching and missionary vocation. Second, there will have to be painful, wrestling and engagement - such as Jacob’s in Genesis 32 and 33 - which will lead to blessing and seeing the face of God but only through costly vulnerability and a brokenness in which grace abounds.

Having set out so clearly what the decisions are and their implications, the bishop’s final words to the House of Bishops – like the final paragraph of the Windsor Report – present ECUSA and the Communion as a whole with a stark and painful choice:

If we find ways of continuing and deepening our journey together the joy will be all the sweeter. And if, God forbid, that is not to be then the tears will be more bitter and the sorrow so much deeper too.

Conclusion

The Bishop of Exeter has, acting as Archbishop Rowan’s representative, given us a much clearer insight into the mind of the Archbishop which has – to the frustration of many on both sides – for some time appeared a closed book. ECUSA has now been put on clear notice that indeed the Windsor Report represents the way of life together in communion and the only context in which ongoing discussion and patient listening over issues of sexuality can take place. The theological rationale often presented to defend the actions of the last General Convention in terms of missiological faithfulness in the American context have been robustly challenged. The attempts to evade the clear and simple calls to ECUSA found in Windsor and repeated at Dromantine have been named and their inadequacy demonstrated. The implications of failure at General Convention are no longer in doubt. It now appears clear that Lambeth recognises the influence of two different but equally destructive anti-Windsor forces (on both sides of the divide over sexuality – group I and group IV) at work in the Communion. These have been unambiguously named and an alternative vision of the way forward together – across the divide over sexuality – described to which people are called to rally. All that now remains to be seen is whether the electors of California and the deputies and bishops at General Convention will truly listen to what the Spirit is saying to the churches of the Anglican Communion and unambiguously embrace the Windsorpath of reconciliation now so powerfully commended by the Bishop of Exeter.