In my graduate studies, my professors had me read great books written by great men who had made a difference in the church and academy. They never talked about the great books that women had written and the great things that women had done. Women’s voices had long been silenced. But thanks to the hard work of many scholars, the great books of many women have been rediscovered and the great things women have done are beginning to be recognised. Their voices can now speak again.

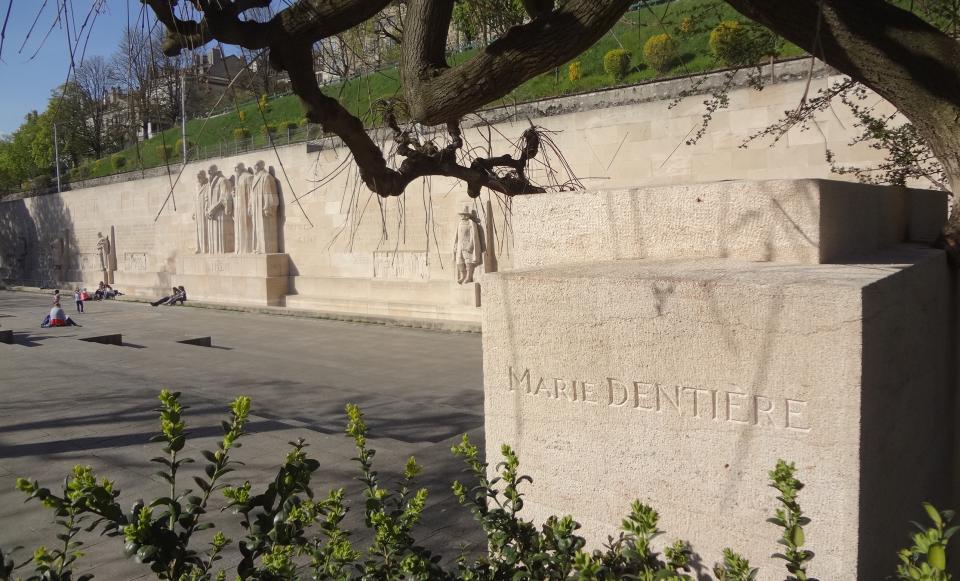

One of many silenced women active during the early years of the Protestant reformation is Marie Dentière (c.1495–1561), a courageous preacher, evangelist, and advocate for the reformed cause. Dentière’s compelling biblical defense for women’s full participation in ministry speaks into debates about women even today.

Dentière appears on the pages of history starting in the early 1520s. After leaving the Augustinian convent in Tournai, Belgium, to join other French sympathizers of Luther’s reform movement in Strasbourg, Dentière married Simon Robert, a former priest from Tournai who fully supported his wife’s gifts for preaching and evangelism. Robert’s support for women in ministry was not widely shared, however. In a letter written in 1528, German reformer Martin Bucer warned Guillaume Farel that “Simon’s wife” expected to be “an active party” in their reformed mission in the Swiss Valais.[1] Five years (and five children) later, Simon died and Marie Dentière married Antoine Froment, a neighboring reformed pastor participating in Geneva’s ongoing reformation.

Although details of Dentière’s participation in Geneva’s reform movement remain sketchy, her contemporaries made derogatory remarks about her preaching and evangelism. In her account of the reformers’ “invasion” of the Poor Clare’s convent in 1535 to convince the nuns to renounce celibacy and leave the convent, Catholic abbess Jeanne de Jussie described Dentière as a “false abbess, wrinkled, and with a diabolical tongue, having husband and children, . . . who meddled in preaching and in perverting people of devotion.” In response to preaching, the nuns “horrified by her false and erroneous words, . . . spat on [Dentière] with loathing.”[2]

In a letter to William Farel in September 1546, Calvin recounted “a funny story” about “Froment’s wife” who had been preaching in the taverns and on street corners of Geneva. In response to Calvin’s criticism of her preaching, Dentière had turned on Calvin and his associates, “complaining about our tyranny [against women], that it was no longer permitted for just anyone to chatter on about anything at all.” She also ranted against their clothing, comparing them to the pretentious scribes Jesus described as liking to “walk around in long robes” (Luke 20:46).[3] In the conclusion of his letter, Calvin justified his contempt of Dentière: “I treated the woman as I should have.”[4]

Calvin couldn’t have been more wrong

As historians now recognize, Dentière was not simply a woman who “chattered” uselessly. She used her impressive knowledge of Scripture and theology in support of Reformation ideals and her expanded vision of women’s roles in ministry. In her most important and inflammatory 1539 pamphlet with the lengthy title, A Very Useful Epistle made and composed by a Christian Woman of Tournai sent to the Queen of Navarre Sister of the King of France, Against the Turks, Jews, Infidels, False Christians, Anabaptists, and Lutherans, which was quickly confiscated, Dentière acknowledged 1 Timothy 2:11-15, verses often cited to silence women. But she also defended women’s right to interpret and teach the Bible: “we are not forbidden to write and admonish one another in all charity.”[5] Committed to the reformation doctrine of sola Scriptura, [Scripture alone], she used biblical examples to counter the view that all daughters of Eve are inherently evil:

Several women are named and praised in holy scripture, as much for their good conduct, actions, demeanor, and example as for their faith and teaching: Sarah and Rebecca, for example, and first among all the others in the Old Testament, the mother of Moses, who, in spite of the king’s edict, dared to keep her son from death; . . . And Deborah, who judged the people of Israel in the time of the Judges, is not to be scorned.

Dentière also highlighted New Testament examples of women preaching, evangelizing, and teaching:

What woman was a greater preacher than the Samaritan woman, who was not ashamed to preach Jesus and his word, confessing him openly before everyone? . . . Who can boast of having had the first manifestation of the great mystery of the resurrection of Jesus, if not Mary Magdalene, . . . and the other women, to whom, rather than to men, he had earlier declared himself through his angel and commanded them to tell, preach, and declare it to others?[6]

A remarkable relational turnaround

Our last glimpse of Dentière from the year of her death (1561) suggests that she and Calvin had come to a place where they agreed to disagree peaceably. Using the pen name M.D., Dentière authored the preface to Calvin’s remarkable sermon on women’s adornment and silencing in 1 Timothy 2: 9-12 that was part of his earlier series on 1 Timothy. Dentière’s preface is generally supportive of Calvin’s concerns about the dangers of extravagant clothes and makeup. She subtly pushes back against Calvin’s association of the sin and the body to explain women’s propensity to dress like “peacocks” and instead presents a more positive view of human bodies. “Using makeup” she writes, “erases the image of God in us, given that the image of God conveys something worth far more than the body’s features.”[7] Then in the closing words of her preface, Dentière sets aside her long-standing theological and practical differences with Calvin. She admonishes readers to listen to Calvin, “the man who preached publicly about that passage, a man who because of the purity of his teachings deserves to be heard among all the ministers and the faithful pastors in Europe today.”[8]

Dentière inspires me to stand up for what I believe. She models a woman who fully embraced the freedom she found in Christ and courageously shared the good news of the gospel publicly. I’m especially touched by her gracious commendation of the teachings of a man who disagreed with her about the position of women in ministry. Dentière’s last act of writing was neither women’s “chatter” nor an act of concession, however, but rather subversion. She refused to hide her talent as she fully embraced her role as a teacher/preacher and espoused her theology that was firmly grounded in her identity as a woman made in the image of God:

If God has given grace to some good women, revealing to them by his Holy Scriptures something holy and good, should they hesitate to write, speak, and declare it to one another because of the defamers of truth? Ah, it would be too bold to try to stop them, and it would be too foolish for us to hide the talent that God has given us, God who will give us the grace to persevere until the end.[9]

*******

Professor Marion Taylor’s most recent book is Voices Long Silenced: Women Biblical Interpreters through the Centuries (Westminster John Knox, 2022). This book, coauthored with Joy A. Schroeder, tells the stories of hundreds of other women who interpreted the Bible from approximately 150 CE to the present. For some of these women, writing about scripture was a dangerous task, as it was forDentière.